Proletkult

Un romanzo di scienza e di fantasia che nessuno avrebbe mai letto.

Forse Proletkult, l’ultimo romanzo di Wu Ming, poteva essere questo. Invece no: partendo dalla figura di Alexander Bogdanov, autore del romanzo Stella Rossa e fondatore del Proletkul’t, ci si addentra nei meandri della Rivoluzione d’Ottobre, durante la sua gestazione e poco prima delle commemorazioni del suo decennale. Ed é proprio Bogdanov a mostrare al lettore cosa vuol dire fare una rivoluzione e pagarne, in qualche modo, il prezzo. Per parafrasare gli autori, non è esattamente un romanzo a là Wu Ming (qualsiasi cosa questo voglia dire). O, forse, si, nella misura in cui un pezzo di storia nostra (nostra in quanto compagni) viene affrontato in modo da darne una visione più personale rispetto a quanto ci si potrebbe aspettare. Lo è anche per la densità degli argomenti: i romanzi di Bogdanov così come gli esperimenti trasfusionali, il Proletkul’t stesso, e tutti i personaggi, storici e non, incontrati aprono degli squarci di interesse enormi.Tutto quello che ho sempre trovato in ogni loro romanzo.

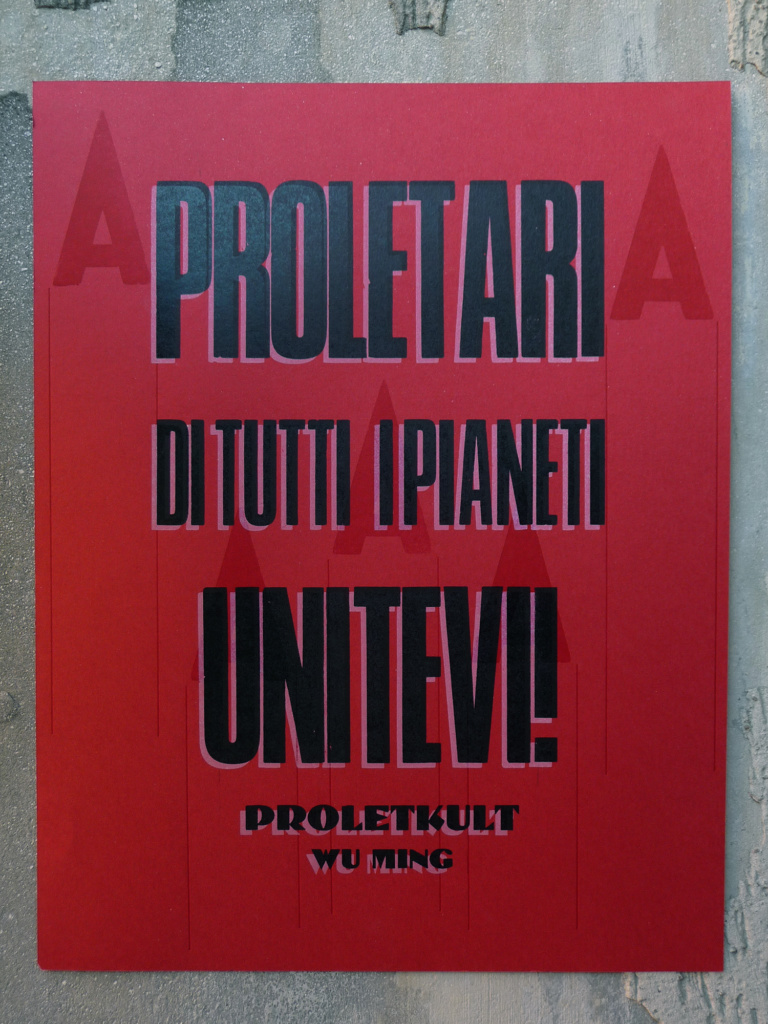

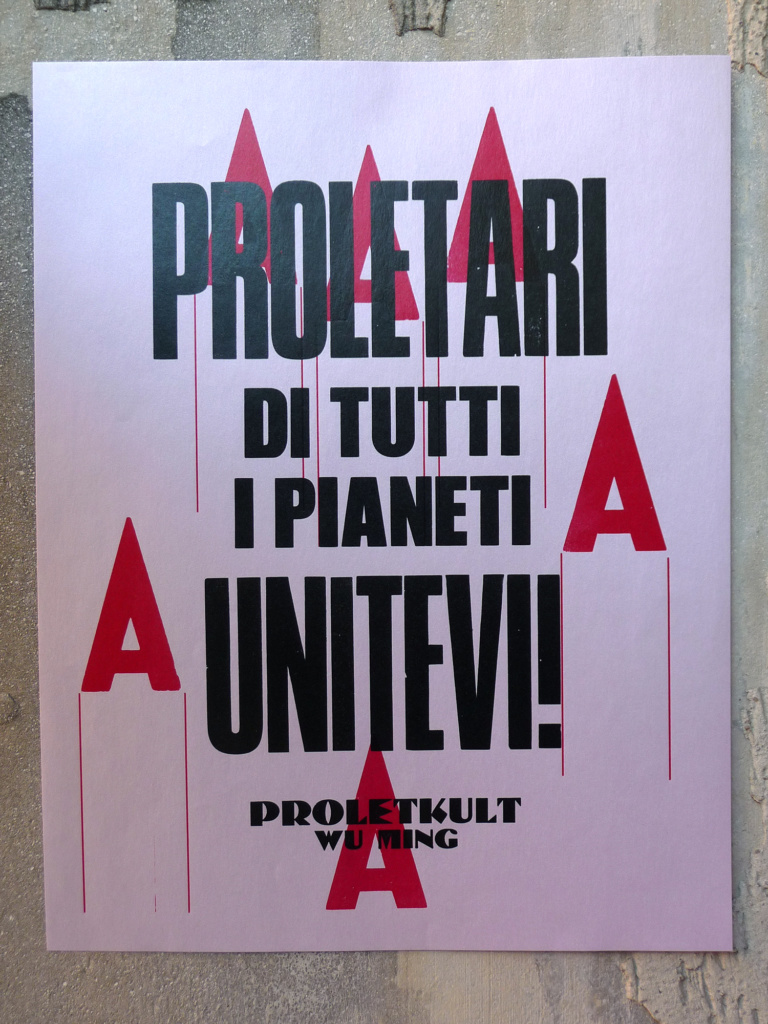

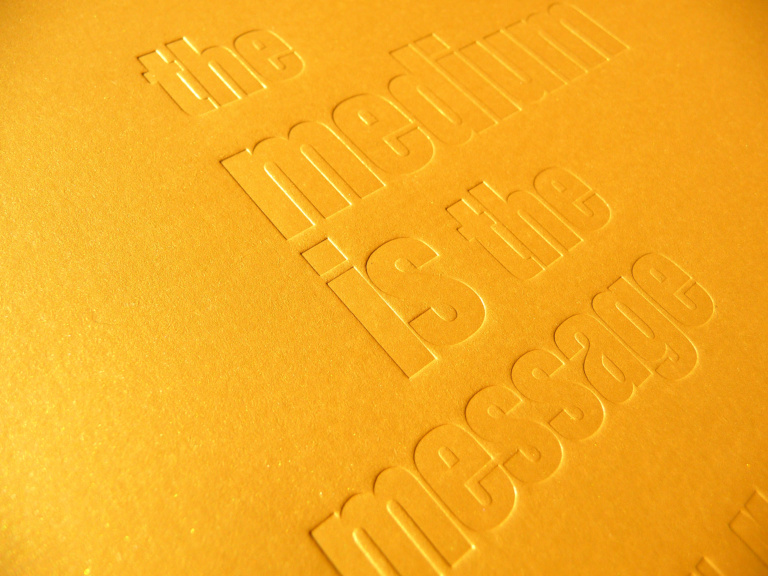

In quanto ai poster, la cosa più interessante è stata quella di rapportarsi (per la verità più come suggestione) con un movimento il cui scopo era quello di dar vita a un’arte creata dai proletari per i proletari. Questo, mescolato con il tema “apparente” della fantascienza, è stato il nodo cruciale. Pensando ad alcune composizioni tipografiche dell’epoca, come quelle di El Lissitzkij, ho utilizzato diversamente alcune lettere, trasformandole in piccole navicelle spaziali. I riferimenti all’idea di modernità dei primi anni del XX secolo si trovano anche nelle carte: quella rossa ha una pasta “brillante”, quella bianca, utilizzata per la seconda edizione, è estremamente metallizzata.

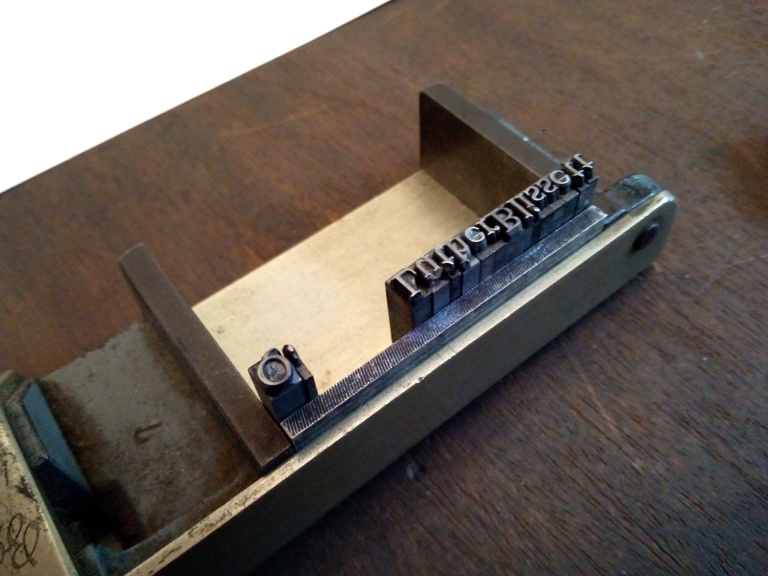

I caratteri non hanno, invece, un particolare retaggio storico. L’esigenza di usare corpi grandi, per dare una buona voce al messaggio, ha fatto cadere la scelta su degli anonimi bastoni (che, comunque, potrebbero essere dell’epoca pure loro). Unico carattere realmente risalente al periodo, con un design che rimanda molto alla tipografia olandese, è il Dolmen, utilizzato per titolo e autore.

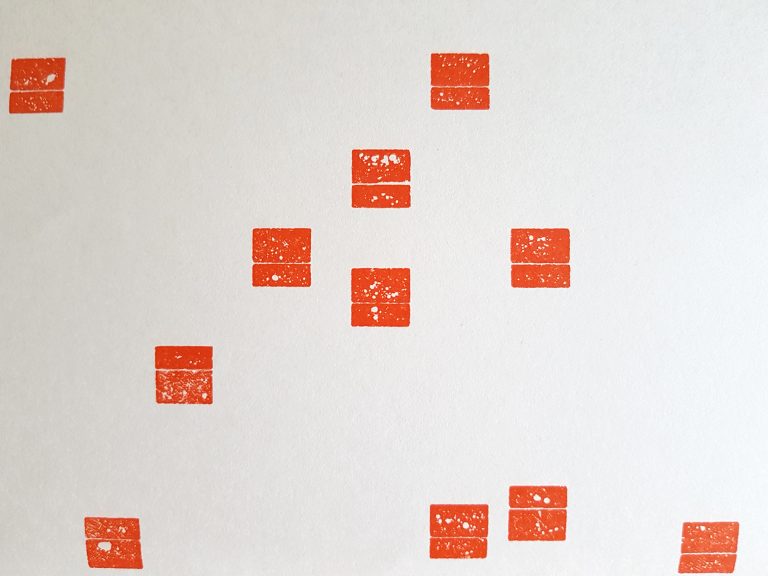

Last but not least, la cartolina, una sorta di esperimento di arte postale al contrario. Ovvero: qualcuno la spedirà realmente, diffondendo così lo spirito della rivoluzione interplanetaria?

Il poster è stato stampato in due edizioni, rossa e bianca (che no, non sono un’omaggio a Bolscevichi e Menscevichi), da 100 copie ciascuna, numerate e firmate. Quella rossa è andata esaurita a gennaio 2019, quella bianca è ancora disponibile (al 25febbraio 2019) durante le presentazioni del libro, insieme alla cartolina.

A science fiction novel that no one would ever read.

Maybe Proletkult, the latest novel by Wu Ming, could be this. Nut no, it is much more: starting from the figure of Alexander Bogdanov, author of the novel Red Star and founder of Proletkul’t, we enter the meanders of the October Revolution, during his gestation and just before the commemorations of its tenth anniversary. And it is Bogdanov himself who shows the reader what it means to make a revolution and pay, in some ways, the price. To paraphrase the authors, it’s not exactly a classic Wu Ming’s novel (whatever that means). Or, perhaps, yes, to the extent that a piece of our history (ours as comrades I mean) is approached in such a way as to give a more personal view than might be expected. It’s also so for the density of the topics: Bogdanov’s novels as well as the transfusion experiments, the Proletkul’t itself, and all the characters, historical and otherwise, encountered open up enormous glimpses of interest. Which I have always found in all their novels.

As for the posters, the most interesting thing was to relate (more as suggestion) with a movement whose aim was to give life to an art created by the proletarians for the proletarians. This, mixed with the “apparent” theme of science fiction, was the point.

Thinking of some typographic compositions of the time, such as those of El Lissitzkij, I used some letters in a different way, turning them into small spaceships. The references to the idea of modernity of the early twentieth century are also in the papers: the red one has a “brilliant” paste, the white one, used for the second edition, is extremely metallic.

The types, on the other hand, do not have a particular historical connection. The need to use big sizes, to give a good voice to the message, made the choice fall on anonymous snares (which, however, could be of their own time). The only one that really dates back to the period, with a design that refers much to Dutch typography, is Dolmen, used by title and author.

Last but not least, the postcard, a sort of experiment of postal art. That is: will someone really send it, thus spreading the spirit of the interplanetary revolution?

The poster was printed in two editions, red and white (which is not a tribute to Bolsheviks and Mensheviks), 100 copies each, numbered and signed. The red one was sold out in January 2019, the white one is still available (at 25 February 2019) during the book presentations, together with the postcard.

More about the novel (italian):

Proletkult

And about Wu Ming (english and other languages):

wumingfoundation.tumblr.com/